tl;dr: American small talk is a perfect example for the definition of Information in Information Theory, and for data compression.

There are things I like more in Germany than in the US. And there are things I like more in the US than in Germany. For example small talk. Small talk is so, so much easier in English – not so much because of the language, but more because of the conventions. You’re not convinced? Let me illustrate my point with the example of a phenomenon I call “repeating phrases.” In the US it’s normal (and even desired, it seems), to repeat the exact same phrase the other person just said:

“Nice to meet you.” – “Nice to meet you.”

“Have a nice weekend!” – “Have a nice weekend.”

In German, never ever would somebody dare to say the exact same phrase again. “Nice to meet you”, one says. And we reply with “Yes, indeed, finally!”, “I’m delighted as well.” or “Likewise!”.

“Have a nice weekend!”, one says. And we reply with “I wish you the same!”, “Thanks, you too!” or “Thanks, the same for you.” At least we would say: “I wish you a nice weekend as well!”, but we would feel a little bit weird about so much repetition.

One could say that Germans are – at least in this regard – more creative and that the English language is – at least in this regard – a little bit dull. But I love it. Why? I’m glad you ask. Two reasons!

The first reason is saved energy. Germans burn more calories while thinking about the answer for standard sentences than Americans. (I’m totally making that up; that is not scientifically proven at all.) Germans need to decide within milliseconds which genius and witty answer they should give to a phrase like “Good night”. Americans, on the other side, can use that energy to wonder about the pattern on the tie of their conversation partner. Repeating what the other side says is like kindergarten. Or like learning a new language: Listen and repeat. “See you later!” – “See! You! Later!”

The second reason why I like repeating sentences so much – and here this post moves from gibberish to educational – is that they contain less information. At the beginning of the year, I was reading James Gleick’s “The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood”. (It’s good. Read it.) He basically wrote a book to answer the question: “What is information?” And one possible answer for that is: “Information is uncertainty, surprise, difficulty, and entropy.”

Wait, what does that mean? Well, let’s take an American “Nice to meet you.” – “Nice to meet you.” and compare its information value to a German “Nice to meet you.” – “You too!” Which of these conversations contain more information? One could think that the American one has more information value, because its a longer string of characters: The American version has 34 characters in eight words: the German conversation only 25 characters in six words.

But Gleick shows that this is not the case: “If a letter can be guessed from what comes before, it is redundant; to the extent that it is redundant, it provides no new information. (…) Paradoxical though it sounded, random messages carry more information.”

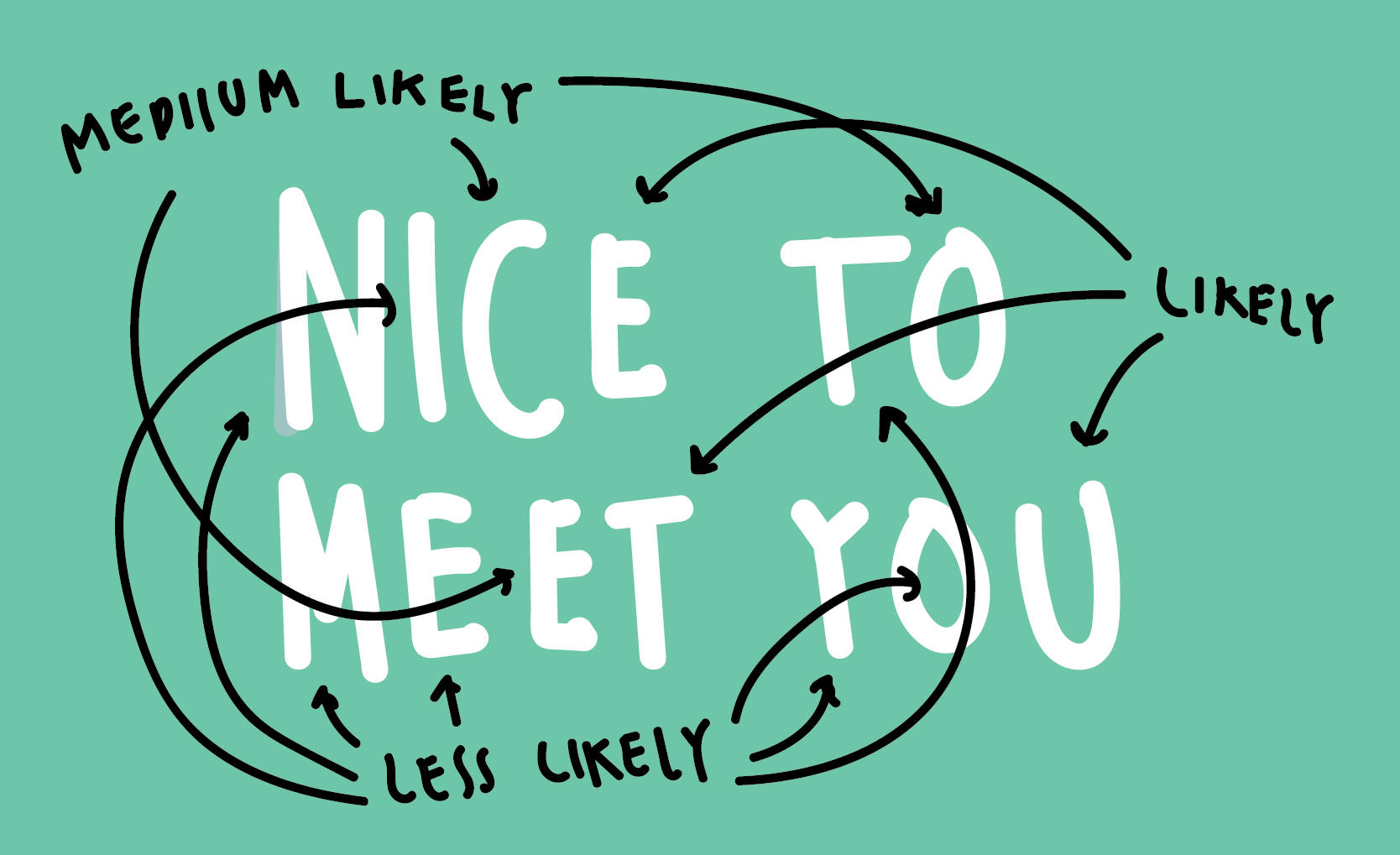

So let’s go through our message with that new knowledge. Let’s start with the first word: “Nice”. When we just see the N, we know that this word will be in the narrowed down space of all English words that start with a “N”. It’s difficult to predict our word from here. There are a LOT of words that start with “N” in English. But if we know that the next letter is an “i”, the space of possible words gets even smaller: It still could be “nil”, “niche”, “nipped” and thousands of other neat words, but it’s more likely now that we can guess the right word (“nice”) than in the beginning of this guessing game. So the uncertainty = information decreases with every letter that we know of a word.

Let’s fast forward and assume we now know that the first two words are “Nice to”. How likely is it that we know that the next word is “meet”? Ok-ish likely. How likely is it that we know that the last word is “you” when we know that the first three words of the message are “Nice to meet”? Even more likely.

Aaaaand, BOOM, how likely is it that the rest of the message is “Nice to meet you” when the first four words of the message are already “Nice to meet you”? In American English: Very likely. In German: Not very likely. The American English comes with less surprise, more redundancy, less difficulty. American small talk contains less information.

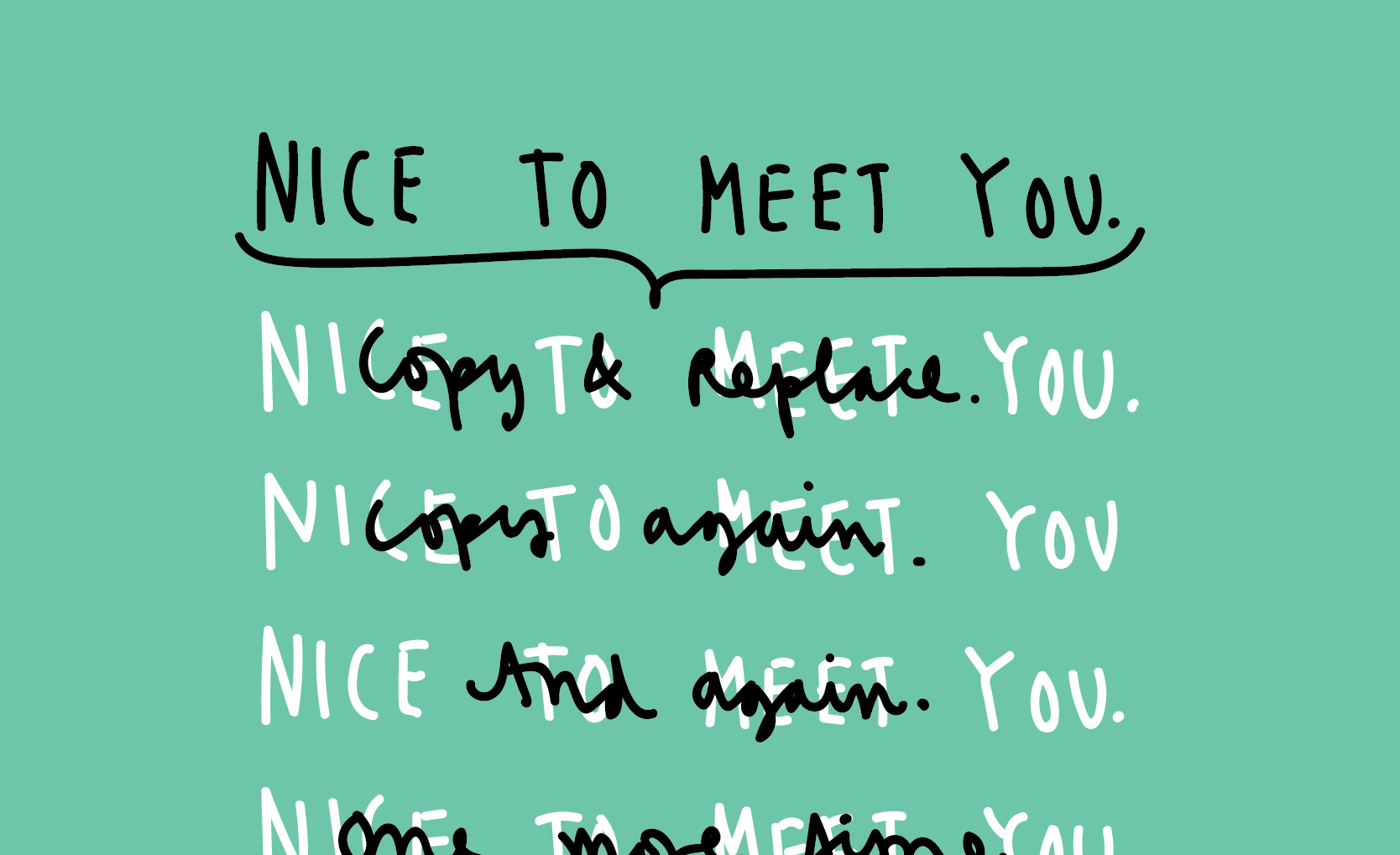

And now, prepare for a fun fact that you can use the next time you’re doing small talk: Data compression (ya know, ZIP, RAR, JPEG, PNG, MP3) is based on this whole “information = redundancy = probability” idea. Compression algorithms like the Lempel–Ziv–Markov chain algorithm create a “dictionary” of used bits and bit phrases, and then predict the likelihood of each next bit. Meaning, the less information a message has, the more compression is possible. It’s impossible to compress a 100% random image.

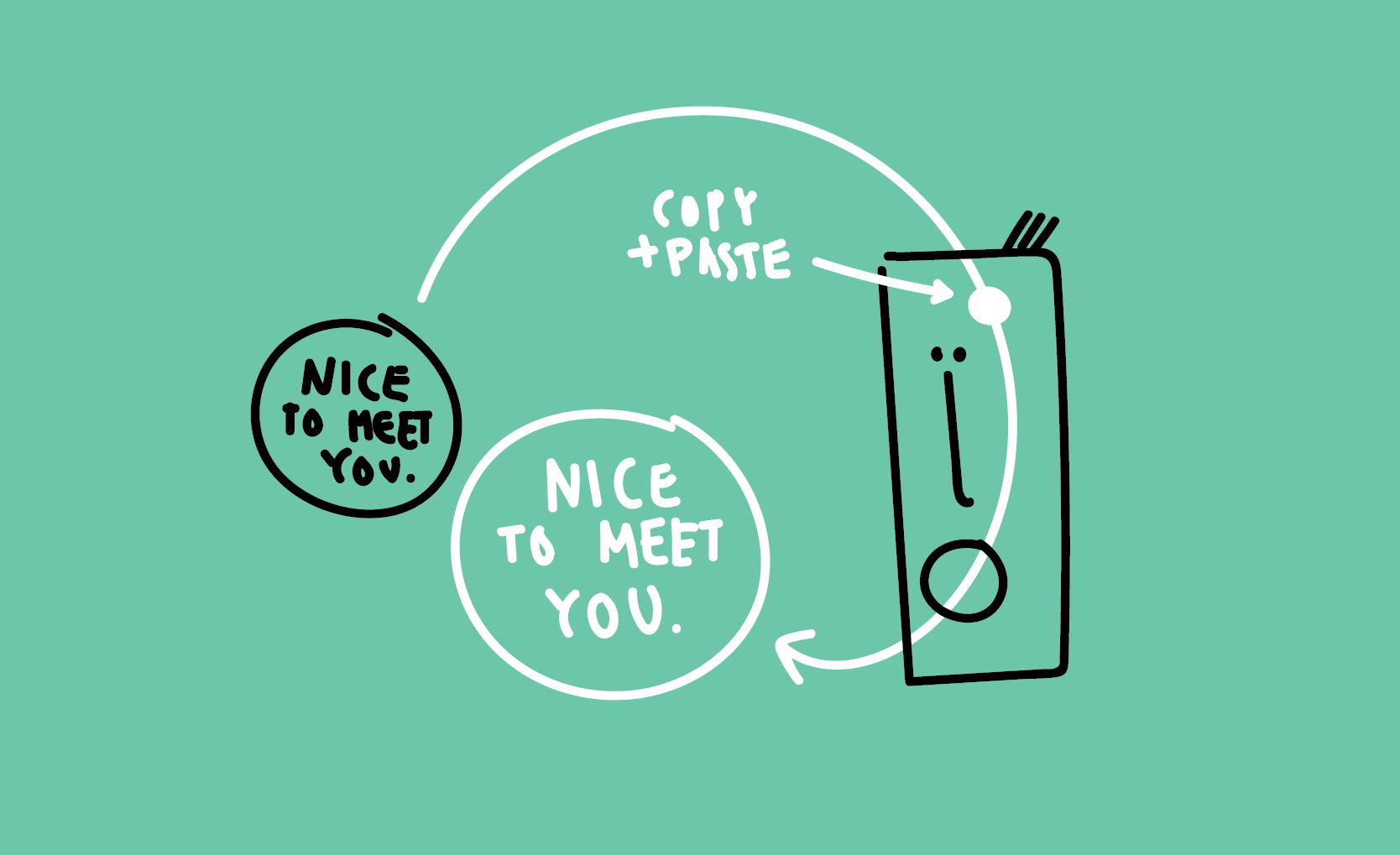

Simply put: After going through the first four words “Nice to meet you”, the algorithms comes to a new capital “N” and thinks (ATTENTION: SIMPLIFICATION, ALGORITHMS DON’T THINK): “We’ve had that situation before! I wonder if the next letter is an ‘i’!” And when it notices that this is the case, it thinks: “Now it’s even more likely that the next letter is an ‘c’!”. And at some point, when the algorithm notices that not only letters, but whole words are repeating, it makes a note à la: “We can just copy and paste the first four words.” In algorithm-speech, that note takes less bytes than actually using the bytes for the letters. And boom: Compression happened.

A good introduction to compression can be found here. Also thanks to Michael Kreil, who was my co-worker at Tagesspiegel and who gave a whole mind-blowing talk about compression in one of our weekly “Let’s teach each other stuff”-talks.

Questions? Hints? Comments? Find me on Twitter (@lisacrost).

Comments