Curiosity. Some people have it a lot, some have it a little. All the data (vis) people I know have tons of it. “I wonder if there’s data out there for it..”, “We could also try to find out…”, “Maybe, if we can prove with data that…” are common phrases you can hear wherever data people gather.

That’s why more than two years ago, I declared curiosity as one of the four core traits of data vis designer:

But although I love the feeling of curiosity while working with data myself, I’ve never considered the curiosity of the data vis reader. That is, until I encountered Tim Harford’s article “The Problem With Facts” a few weeks ago. He cites a paper that studied the effect of curiosity on reasoning:

Robin Kwong transformed this idea in his article “How do we create a need for news?”:

Help people to explore the world? Help them to learn about it? Not giving final answers to people, but making them ask questions? That seems like a goal worth pursuing for journalism.

But I’m conflicted.

On the one hand: Yes, curiosity is amazing. Why? Often, curiosity is directed towards something very specific. It comes with a concrete goal: Finding out what happens when you jump in that puddle. Finding out if your best friend has a new boyfriend. Finding out if there’s a regional pattern with unemployment rates in your country.

Having these intrinsic motivations and acting to get there is one of the best feelings in the world. It’s what people talk about when they talk about “Flow”. You forget the time. You feel productive. Your work feels important and meaningful. There’s just you and the goal. And everything you do is to reduce the obstacles between you and the goal. And when you reach the goal, a mini-Christmas is happening.

I want readers to get that feeling when they interact with my data visualizations. I want them to feel curious about the data. I want them to ask questions, and to find answers. I want them to feel empowered, and to really grasp the data.

On the other hand, I want to make sure that they get the most important statements in my data vis. I want to save them the time to figure out these points on their own. They shouldn’t learn how to use a completely new data vis tool, just to get to an underwhelming point after half a day of digging. My job is to spend all that time with the data for them, so that they don’t need to spend that time themselves. I want to deliver answers to them, fast.

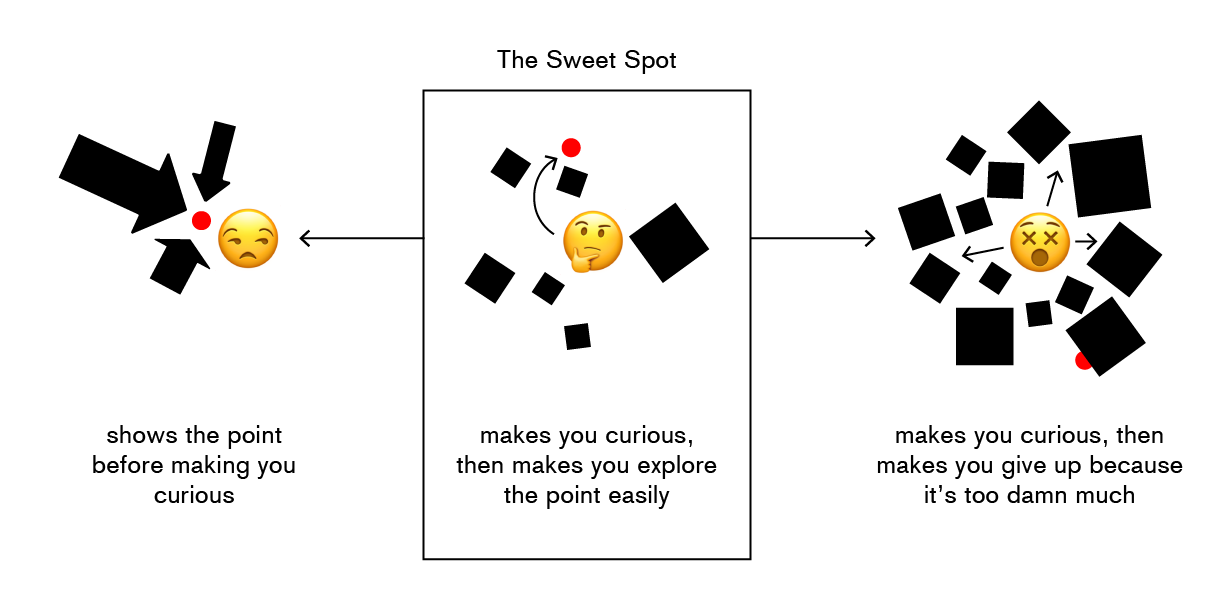

A compromise is needed. I think I need to say goodbye to the idea that the most efficient data communication is always the best way to go. For people to care about my data, I need to make them curious, first – to the right degree:

There is a sweet spot between my current “get the reader the information the fastest, even if that means it’s a bar chart”-mindset and the too-open field of wonder in which the reader will quickly lose interest; especially if he doesn’t know if it’s worth it.

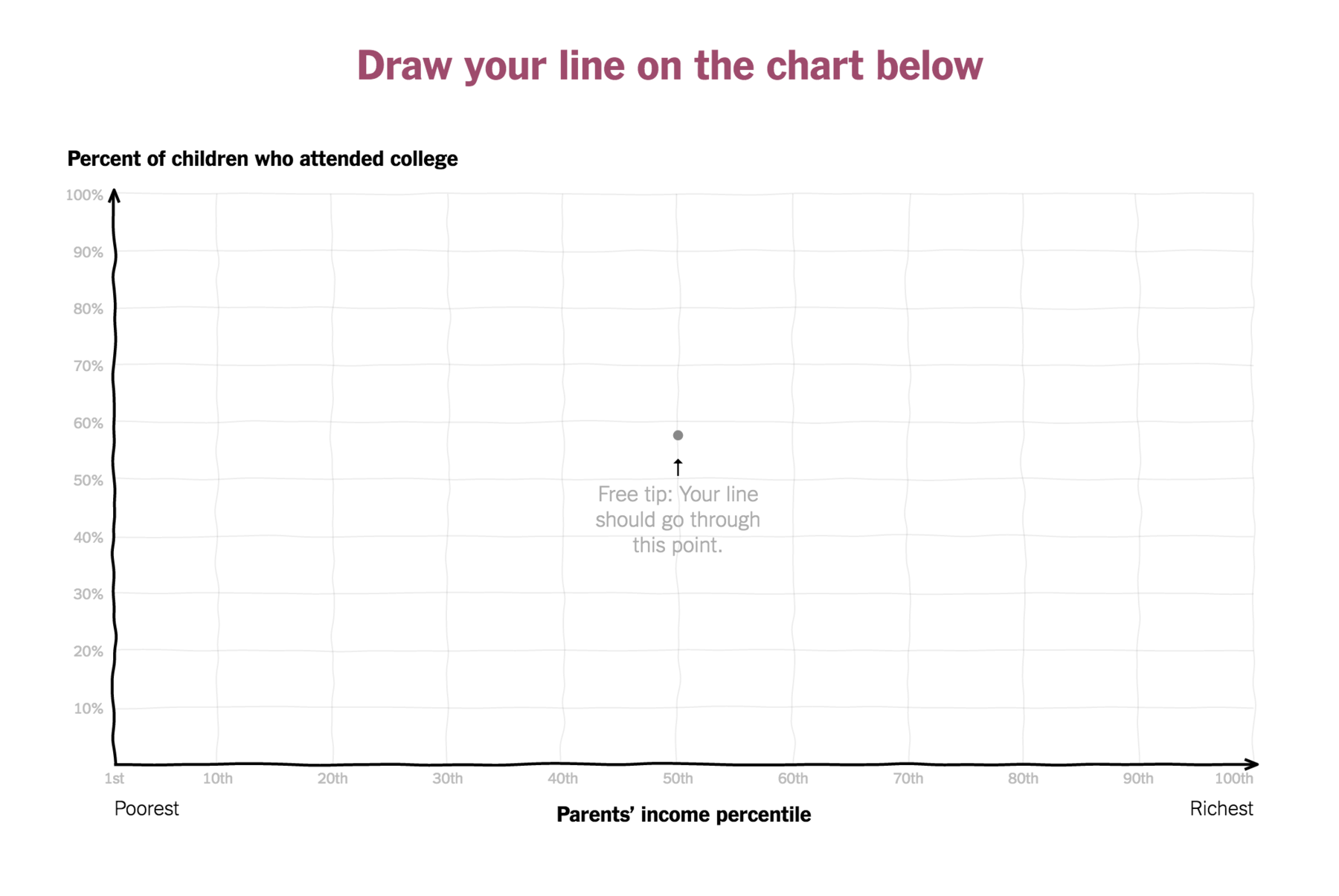

That sweet spot has been hit by many people in the past. Explorable Explanations have been doing that really, really well. And in the news graphic realm, the New York Times did an amazing job with their “You Draw It” graphic:

It’s a quizzing tool that plants a question in the reader, before showing her the information. The reader needs to build a hypothesis first. Then she can check if her belief was right or wrong. It’s science in a mini-format.

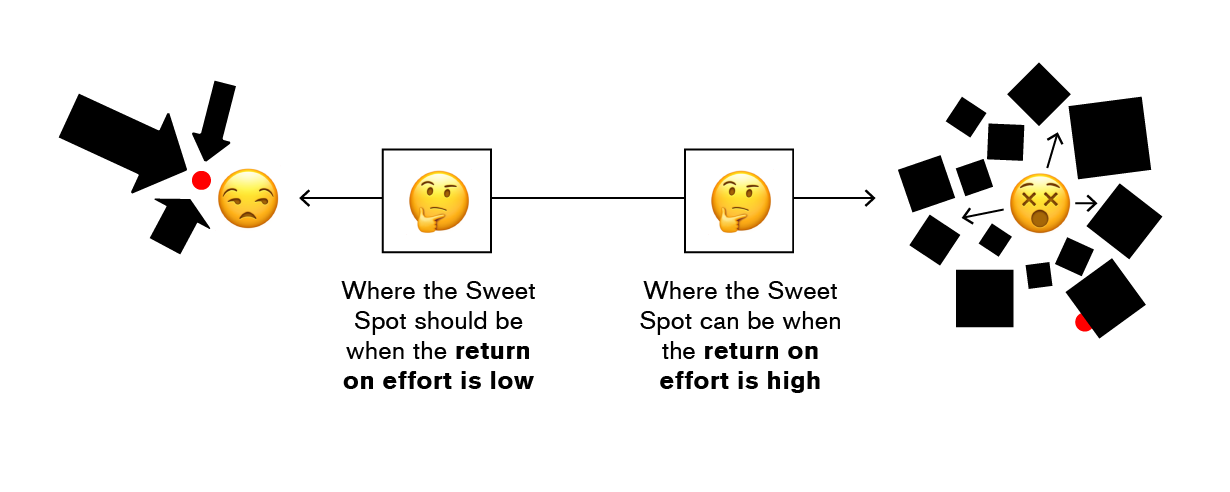

But it’s science that’s rewarded. The reader trusts the NYT that it will be worth it to work for the answer; that the question the reader asks will lead to an interesting answer. Not every data is worthy of such a treatment. In 2011, Kaiser Fung introduced the metric “return on effort” for evaluating graphics. He asked: How much will the reader be awarded for her effort to read the graphic? The reader will be annoyed to work for her insight if the insight is disappointing. We need to adjust our work to take that into account:

When we first make a reader curious and then deliver the answer, we can have a greater impact than when we just deliver the answer. The question is: What are good ways to make people curious? What are ways to plant questions in people’s head? How can we make people curious about the world, even the ones who don’t score high on curiosity naturally?

And to think one step ahead: Can we, instead of giving people answers, or first plant questions and then answers – can we give people the questions without the answers? Questions we don’t have any answers for yet? How can we empower people, and make them interested in trying to solve the yet-to-be-solved problems?

Curiosity is like a superpower of people. When curiosity is fired up, people seek out information actively and suck it up like a sponge. Let’s make sure we understand and use that power.

Please help me to answer these questions. Write me an email (lisacharlotterost@gmail.com) or find me on Twitter (@lisacrost).

Comments